As digital ecosystems surge - spanning more platforms and millions of participants - verifiers are stepping into fully online workflows where issuers, holders, and relying parties interact at speed and scale. The core challenge is deciding what to trust without becoming a giant data warehouse. The rule is simple, the practice is disciplined:

trust, but verify.

In IXO and similar ecosystems, you can’t rely on PDFs or screenshots; you must check who issued the credential, validate the digital signature, understand the evidence and assurance level, and confirm status and freshness - all while minimising what you collect and preserving privacy.

A growing complication is duplicate personal data: people often hold multiple credentials containing the same sensitive details (e.g., national ID numbers) across different programs. Duplication amplifies exposure, raises privacy risk, and makes compliance trickier. Wherever possible, use pseudonymous or scoped identifiers and ask for proofs that confirm claims (like “ID verified”) without revealing full raw data. Whether you’re new to VCs or helping a fast-growing ecosystem keep its footing, applying these practices lets you onboard quickly and make sound, auditable decisions at scale.

What Is a Verifiable Credential, Anyway?

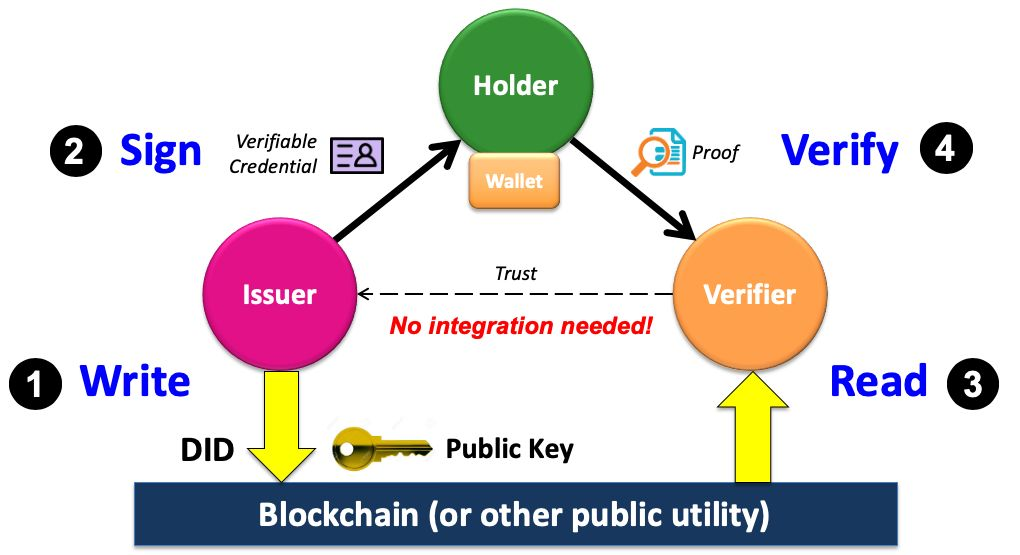

Think of a Verifiable Credential (VC) as a super-secure digital letter on official letterhead. Three roles are involved: the issuer (a government program, NGO, company, or individual) signs and vouches for the content; the holder keeps it in a digital wallet; and you - the verifier - check whether it’s legit.

The reliability comes from cryptography and open standards. VCs follow the W3C Verifiable Credentials Data Model (VC DM), and issuers are identified by Decentralised Identifiers (DIDs) defined in the W3C DID Core specification. Your verification tool resolves the issuer’s DID to fetch their public keys, then validates the digital signature and integrity - no phone calls or screenshots required.

Many VCs also include evidence (what checks were done) and a status you can query - commonly using W3C-aligned mechanisms such as VC Status List 2021 - to see if the credential is revoked or suspended. Together, these let you make fast, risk-aware decisions while minimising data - often proving what’s needed (e.g., “ID verified = Yes”) without exposing full personal details.

Verifiable Credential Trust Triangle - How VCs are created and used.

1) Register the issuer: The issuer publishes a Decentralised Identifier (DID) and its public key (plus any required cryptographic metadata) to a blockchain or other trusted public registry.

2) Create a verifiable credential (off-chain):

- Scope the claim: decide what the VC will assert and the privacy rules it must follow.

- Collect evidence: from self-assertions to checks against documents or authoritative databases.

- Bind to subject: the holder proves control of a key or identifier linked to the claim.

- Construct & sign: the issuer assembles the VC with timestamps and evidence, then signs it digitally (issuance occurs off-chain for privacy).

- Publish status: maintain a status record so revoked or suspended credentials can be flagged.

3) Request and present proof: A verifier asks the holder for proof of one or more credentials. With consent, the holder’s wallet generates fresh proof(s) and returns them, including the issuer’s DID. The verifier resolves that DID to obtain the issuer’s public key and related cryptographic data.

4) Verify: Using the issuer’s public key, the verifier validates the signature and integrity of the proof and checks status to confirm the credential hasn’t been tampered with or revoked.

Assurance - choosing “enough” proof for the decision

“Assurance” is simply: what evidence backs the claim, who collected it, how you can audit it, and whether it can be revoked or updated. Pick the assurance that matches the risk of your decision - no need for numbered “levels.”

Common assurance patterns:

- Self-attested: The holder asserts the fact themselves. Useful for low-stakes onboarding or community features.

- Issuer-verified: A recognised program/organisation checked some evidence (e.g., documents reviewed by staff, presence verified at an event). Good for routine access and non-cash benefits.

- Authoritative-source-verified: The claim was checked against an official or system-of-record source (e.g., government registry, accredited database) with audit trail and revocation. Use for money movement, sensitive services, or legal identity.

When to require stronger assurance (illustrative):

- Low risk (discussion forums, basic participation): self-attested may be fine.

- Moderate risk (repeated access, non-cash benefits, program compliance): issuer-verified.

- High risk (funds disbursement, regulated KYC, safety-critical access): authoritative-source-verified plus online status checks and explicit auditability.

Don’t forget currency & privacy:

- Set freshness expectations (e.g., re-present identity credentials within a defined window).

- Always prefer data minimisation/selective disclosure (e.g., “ID verified = Yes”) over exposing raw identifiers.

Managing Duplicate Info Across Credentials

Duplicate personal info - like the same ID number appearing in several credentials - is a real privacy headache. It increases exposure and can make compliance with laws like POPIA and GDPR harder.

Best practice? Use scoped or pseudonymous identifiers that are unique per program but don’t expose raw personal data repeatedly. Ask for “ID verified” flags or last-4 digits instead of full numbers. Focus on the trust level behind the claim - not just the data itself.

You Are the Verifier: What Should You Check?

When you get a VC, simply ask yourself:

- Who issued it? Is this issuer known and authorised? Check Domain Cards or registries.

- Was it really signed by them? Your software should verify the issuer’s DID and signature.

- What evidence supports it? Self-attested? Program-checked? Officially verified? Look for clear evidence statements.

- Is it current? Check issuance date, expiry, and revocation status.

- Is it bound to the right person? Do subject identifiers match? Did the holder prove control?

- Is the data appropriate? Can you accept a “verified” flag instead of full personal info?

- Does the assurance level fit your risk? Match your checks to what’s at stake.

Real-Life Examples

Example 1: A youth shows an Impact VC claiming they contributed to a project, including a self-attested national ID (no external check).

Accept the contribution claim if the evidence and issuer are solid, but treat the ID as unverified. For matching across systems, prefer pseudonymous program-scoped IDs. If you must verify legal identity, ask for an Authoritative-source-verified VC instead.

Example 2: The youth presents a verified identity VC with a national ID, issued after document and database checks by an authoritative-source-verified.

Trust it if issuer authority checks out, signature is valid, status is good, and it’s fresh. Prefer selective disclosure or “ID verified” flags, and keep an audit log instead of storing raw IDs.

How to Put This Into Practice

To put this into practice, build a disciplined routine: always confirm who issued the credential via DID and signature, understand the evidence and whether it matches the risk of your decision, check status and freshness, and minimise what you store by preferring selective disclosure and simple “verified” flags over raw identifiers. For legal or financial decisions, require stronger assurance and shorter freshness windows. Publish clear policies so issuers know exactly what standard you’ll accept.

Verifiable Credentials let you verify claims quickly while preserving privacy and reducing risk. Keep raw data separate from the trust decision: validate the issuer, review the evidence, confirm status and recency, and lean on pseudonymous or scoped identifiers wherever possible. Applied consistently, these habits scale trust safely and fairly - and support fast, auditable decisions at any size.

How the IXO Protocol leverages Verifiable Credentials: